The Blaffer Family

Robert Lee Blaffer of Houston, Texas, was a wealthy, influential man, who made his fortune in the oil business. He started out drilling for oil with his own hands and went on to become one of the founders of Humble Oil, which later affiliated with Standard Oil and eventually became part of Exxon.

His wife, Sarah Campbell Blaffer, was the daughter of William Thomas Campbell who had also got his start drilling his own oil wells. He later became one of the signers of the original charter for the Texas Company—Texaco.

Mr. and Mrs. Blaffer had four children: John, Jane, Cecil and Joyce. The family would normally have spent their summer vacation in Europe but, in 1939, the war prevented them. Instead, they visited Canada.

When Mrs. Blaffer passed by the Keeler farm, she was captivated by the breathtaking view. She made arrangements to purchase the property and engaged the Keelers to stay on for a time as caretakers.

A few weeks later, Mrs. Blaffer also purchased the farm to the west which was owned by Ernest Joice. The Joice family stayed in the house until the following spring when the Keelers took up residence there. The Joice’s red-brick home (built by Simon Jayne) is now part of Ste. Anne’s Inn—known as the Farmhouse and the Gables.

She wanted a comfortable, relaxed environment, large enough to accommodate her family, live-in staff, and other visitors. Her concept was to create a house which would resemble the old stone cottages she had seen and admired in the Cotswold district of England. She hired an architect to help her design the additions. The architect was Mr. Abbott from New York, who also had a summer house in nearby Cobourg. He told the Blaffers he believed the original house was the work of a Scottish stonemason because of the large, squared stones used and the construction technique. Therefore, a Scottish stonemason—Mr. Skillen—was found to oversee the construction of the additions.

Mrs. Blaffer wanted to match the uniquely-coloured pink of the original house if possible. Men were dispatched to canvas the neighbourhood for suitable stones. Area farmers happily offered them from their fields and fence lines, but used stones, already cut, were preferred. Therefore, stones from abandoned foundations of former houses and barns were collected. The stones of the original Academy Hill School, long abandoned, were purchased for the construction of the additions.

That school had been replaced years earlier by the red-brick building at the top of the hill, which is now also part of Ste. Anne’s Inn and known as Haldimand East and Haldimand West. However, the quantity of used stones or boulders massive enough to be worked into two-foot squares could not be found. The additions were built with timber framing and finished in random stone. In some of the later additions, the stones are so small the result resembles cobblestone.

Very likely, before construction even began it was the talk of the surrounding area. “What ever are they going to build with all those stones?” By the time the structure was completed, the neighbourhood regarded it with such amazement that it was given a nickname. Mrs. Blaffer’s stone cottage became known as the Grafton Castle. The Blaffers gave their summer home its true name, the name it still carries today—Ste. Anne’s. Mrs. Blaffer’s daughter, Jane Owen, explained why this name was chosen. She said,

Our family believes in divine healing and in the protection of our saints.

It was she who suggested honouring the patron saint of Canada—Sainte Anne de Beaupré.

Construction proceeded through the winter of 1939-40. Mrs. Blaffer visited to see the progress and spent an enjoyable day driving over the whole property in a horse-drawn sleigh.

Ethel Winter, Ernest Joice’s daughter, grew up in the red-brick farmhouse to the west. A few years after the main additions were completed, she worked for Mrs. Blaffer as a housekeeper for three summers. During the winter of ’39, she and her family still lived next door. She provided this account:

The marble floor [for the dining room] was brought up from the States in the winter of 1939/40. The truck became stuck in the snow, and my father and a couple of neighbours took the horses and sleds, and brought the slabs up to the farm. The marble was heavy, and the snow was deep, and it was quite a chore.

The addition to the west had bedrooms on the upper floor. The main floor contained the dining room, with its black and white marble-tile floor, a fireplace, and French doors onto the north courtyard. Beyond the dining room was a butler’s pantry and the kitchen. To the east, a library was built and connected to the original house by a stone arch. This grand archway had a very practical purpose. It provided a shady spot that was always breezy on hot summer afternoons. The family often gathered there to shell fresh peas for supper.

The original house also was renovated. Rooms that previously had only wood stoves were given fireplaces. These and the existing fireplaces were fitted with refined, hand-carved mantelpieces brought from Pennsylvania. The front door was replaced with a six-panel door also brought from Pennsylvania. Sometime later, that doorway was altered to the bowed style and double glass doors are still present. Electrical wiring and plumbing were installed and the house had indoor bathrooms for the first time.

The addition to the west had bedrooms on the upper floor. The main floor contained the dining room, with its black and white marble-tile floor, a fireplace, and French doors onto the north courtyard. Beyond the dining room was a butler’s pantry and the kitchen. To the east, a library was built and connected to the original house by a stone arch. This grand archway had a very practical purpose. It provided a shady spot that was always breezy on hot summer afternoons. The family often gathered there to shell fresh peas for supper.

The original house also was renovated. Rooms that previously had only wood stoves were given fireplaces. These and the existing fireplaces were fitted with refined, hand-carved mantelpieces brought from Pennsylvania. The front door was replaced with a six-panel door also brought from Pennsylvania. Sometime later, that doorway was altered to the bowed style and double glass doors are still present. Electrical wiring and plumbing were installed, and the house had indoor bathrooms for the first time.

The back section, which had been the kitchen and dining area for the Keelers, became Mrs. Blaffer’s sitting room. The walls, floor, and ceiling were all painted yellow, and a fireplace was added. What had been the living room became Mrs. Blaffer’s bedroom. It had a French door which looked out into the walled garden. One room across the hall was converted to a bathroom. The other room across the hall served as private quarters for Mademoiselle Glemet. Mademoiselle had been governess for the Blaffer children but, as they grew to adulthood, she stayed on with the family in the position of “household chatelaine”.

Jane Owen recalls that one of the upstairs rooms, the one at the back, required some extra work. Its doorway had to be knocked out and enlarged. The room had a very narrow entrance, and Mr. Abbott explained that this was not uncommon. Many early Ontario homes had rooms designed to be easily fortified hiding place in case of Indian raids. (These rooms were usually concealed areas in the basement, accessed by trap doors. This precaution was more a response to stories about the Indian wars in the States than to any actual danger in Canada.)

When construction was completed, the walls were hung with mirrors and many paintings. Mrs. Blaffer was well known as a patron of the arts. However, the house was furnished sparingly in keeping with its purpose as a relaxing summer retreat. Many pieces of simple, sturdy Habitant furniture, in butternut or pine, were purchased from Quebec. The library, painted salmon pink, had tall bookcases in its corners. Leather chairs and a large, circular gateleg table sat in the middle of the room.

Ethel Winter remembers that Mrs. Blaffer’s bedroom had a four-poster bed and a long writing table with green leather inlay, banded in brass. She recalls being especially impressed by a desk in the sitting room, which was green with gilt trim. It was eighteenth-century pine and had been brought from Quebec.

The north courtyard was enclosed with a high stone wall, which added to the impression that Ste. Anne’s was a convent or monastery. The walled garden, like the cottage-styled additions, was typically English. Mrs. Blaffer had the wall topped with clay pots of pink petunias and hollyhocks and delphiniums grew at the base. In summer, the terrace facing Lake Ontario blazed with the colours of portulaca growing in the cracks between the flagstones. The wall gave the courtyard a secluded feeling and sheltered the garden’s flowers from harsh winds.

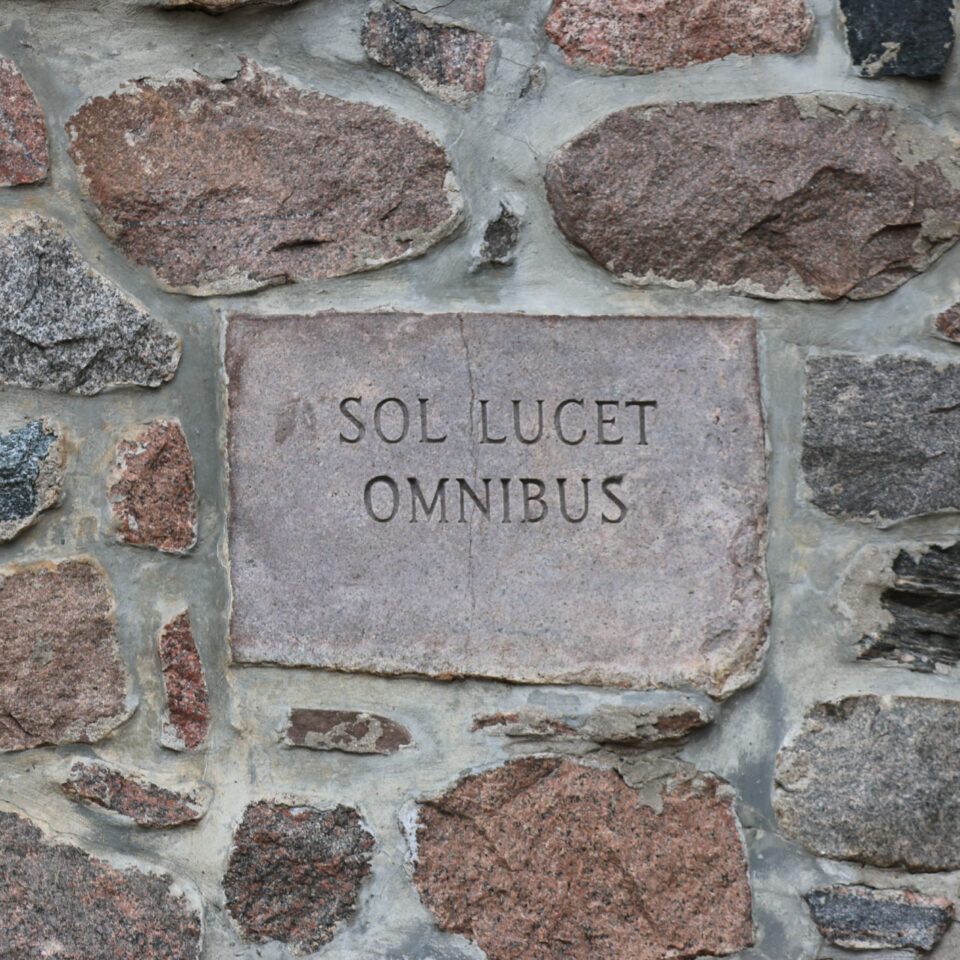

The stone is carved with the Latin words Sol lucet omnibus. Thus, the farm once called Sunnyside was given a broader meaning: The sun shines for everyone.

The construction at Ste. Anne’s continued for several years and provided work for many in the area. A garage was built to the west of the house. Beyond that, there was a vegetable garden and orchard. Southwest of the garden, a stable housed two milk cows and some chickens, along with a small herd of cattle. There were sheep on the farm at one time, too.

The stable was the bottom level of what had been Mr. Joice’s hiproof barn. The tall barn interfered with the view, so Mrs. Blaffer had the top level removed and a roof put over the foundation. A new well was drilled in the low area to the south of the house, finally tapping Ste. Anne’s hidden treasure—abundant, pure water, deep underground. Enclosed in the original stone pump house, that well is still in use today and provides all the water for the inn, including the swimming pool.

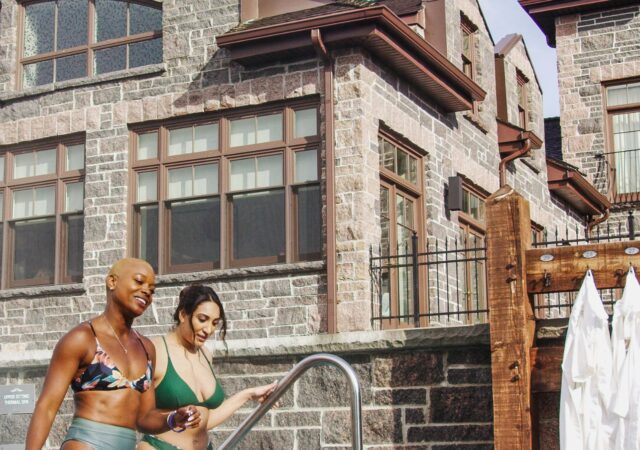

The swimming pool, amazingly, was installed by Mrs. Blaffer almost sixty years ago. She loved to swim and was often observed walking across the lawn in a long, flowing robe, which she slipped off just before diving into the pool. Mr. Blaffer retired in 1941.

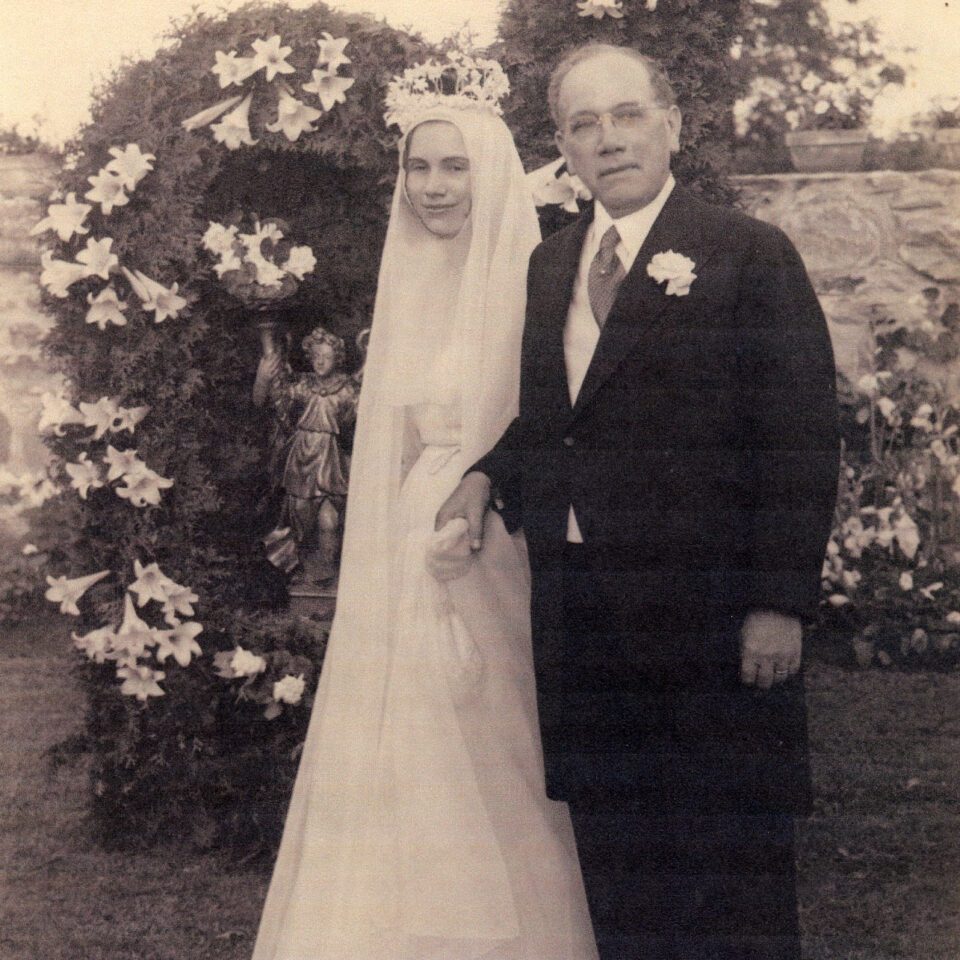

An addition was built on the east end of the house called the Wedding Room by the Blaffers, it is now known as the East Suite. When it was built, it had a fieldstone floor to accommodate dancing after the wedding. Mrs. Blaffer planned the details so carefully she even timed the planting of buckwheat. The day of the wedding, the fields surrounding Ste. Anne’s were snow white.

The ceremony took place outdoors and was conducted by Reverend Nind from St. George’s Church in Grafton. The bridesmaids wore chiffon dresses in shades of pink, lavender and white, echoing the colours of the petunias in the garden.

As a tribute to the newlyweds, they flew in “V” formation over Ste. Anne’s, dropping messages of goodwill.

Many guests to the wedding came from far away, but all the farmers from the neighbourhood were also invited. Mr. Waldie, who raised ducks and geese on his farm across the road, presented the couple with an eiderdown quilt, which Mrs. Owen has to this day.

The following summer, Jane Owen was visiting her parents at Ste. Anne’s when her daughter Janie was born. Just three weeks later, they were preparing to return to their home in the States. Mr. Blaffer wanted to do something special for his daughter and new granddaughter. He went to Toronto to exchange their regular train ticket for a private coach so they could travel more comfortably. Sadly, he suffered a heart attack while he was there and died. Mrs. Blaffer continued to spend her summers at Ste. Anne’s and her children came to be with her. Jane Owen’s second daughter also was born there. Mrs. Blaffer was never happier than when her grandchildren came to visit. She had a playhouse built for them to the east of the main house. The design for this circular stone house was taken from a French dovecote, called a pigeonnier. For symmetry, a matching stone building was added to the west side of the house. It held the laundry facilities.

The winter of 1943, Mrs. Blaffer arranged for a local family to stay in the home. She was apparently concerned that struggling back and forth through the snow to check on the building would be too taxing for Mr. Keeler. (The family who stayed to take care of the house was Lawrence Jaynes, his wife and four youngest daughters, relatives of the former owner, Simon Jaynes.)

Mr. and Mrs. Keeler decided it was time to retire in 1945. Harold Winter (brother in-law to Ethel) and his wife, Ada, moved into the red-brick farmhouse and became caretakers for Ste. Anne’s and its farmland, duties they were to carry out for over thirty years. Harold Winter managed many of the farm duties, but Lawrence Jaynes and his son, Clarence, often were hired to cultivate and harvest.

Mrs. Blaffer’s appreciation for Mr. and Mrs. Winter’s service continued after her death. Her estate provided a pension for them and, even after they retired, ensured lifelong accommodations. Mrs. Blaffer became friends with many people in the area, and over the years there were many guests at Ste. Anne’s. She enjoyed entertaining her company with fine dinners followed by concerts or evenings of song.

A famous painter, Milton Avery, and his wife, Sally, visited Ste. Anne’s in 1947. The Averys were on their way to a vacation out west and stopped by only to deliver a painting Mrs. Blaffer had purchased from him. She persuaded them to stay three weeks and sent her chauffeur to Toronto to get additional art supplies. Mr. Avery painted scenes in and around Ste. Anne’s and many of his paintings and drawings are attributed to this time. His painting of a white capon, done at Ste. Anne’s hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art.

Other well-known visitors included Vincent Massey (Governor General of Canada from 1952 to 1959), who paid a visit to Ste. Anne’s with his daughter in the late 1950s. Vincent Massey was the great-grandson of Daniel Massey Jr. who was Samuel’s uncle. While visiting the area, Mr. Massey observed that the Academy Hill Cemetery, where so many of his relatives were buried, had fallen into a neglected state. Stones had been damaged, toppled, and displaced. He had the cemetery restored and thestones were arranged as they are today. After 1967, Mrs. Blaffer’s failing health prevented her from visiting Ste. Anne’s. The summer house was closed and the paintings were removed to a gallery in Cobourg for safekeeping. Even so, the original bell from the stone wall was stolen and break-ins and vandalism were always a concern. Harold Winter began sleeping overnight in the big, empty, old house to prevent further damage. Sarah Campbell Blaffer died at age ninety-one. She left many legacies to be enjoyed by everyone. Her impressive art collection, works of the masters and of American abstract expressionists, was exhibited throughout the States. In Canada, she left at Ste. Anne’s, her own work of art, as an example of her desire to preserve the best of the past.

In July 1975, a few months after her mother’s death, Jane Owen visited Ste. Anne’s for the first time in eight years. She was interviewed by a reporter from the Cobourg Star during that visit. Mrs. Owen spoke about many happy memories of her family’s summer house. She said then that she was hoping to revive Ste. Anne’s and encourage her relatives to begin visiting again. That did not happen. The family had summer houses elsewhere and Jane Owen began concentrating her energies on the restoration of a small town in Indiana—New Harmony—which her husband’s ancestor, Robert Owen, had purchased in 1825.

Ste. Anne’s stood empty for six years more.